Paid a visit to Haunch of Venison's new show on Friday, featuring the work of Keith Coventry and Adrian Ghenie. I'm always slightly apprehensive before I walk in to a modern art gallery. I really, really want the work to be good, but experience has so often brought disappointment. I suspect the Tate Modern is largely to blame. Let me explain. Because the Tate is the biggest, most prominent, extensively funded space for the display of modern art in the entire country, one might expect it to - like one's parents before one is old enough to realise parents have affairs and neglect to use contraception - hold some degree of authority and expertise. Yet in the last two years, all but one of the Tate Modern's exhibitions have filled me with dread, apathy at the very least.

Paid a visit to Haunch of Venison's new show on Friday, featuring the work of Keith Coventry and Adrian Ghenie. I'm always slightly apprehensive before I walk in to a modern art gallery. I really, really want the work to be good, but experience has so often brought disappointment. I suspect the Tate Modern is largely to blame. Let me explain. Because the Tate is the biggest, most prominent, extensively funded space for the display of modern art in the entire country, one might expect it to - like one's parents before one is old enough to realise parents have affairs and neglect to use contraception - hold some degree of authority and expertise. Yet in the last two years, all but one of the Tate Modern's exhibitions have filled me with dread, apathy at the very least.But since HOV has moved into its new home, I've arrived at each exhibition with a tingle of dread and departed with a satisfied sense of encountering artists of both great talent and great wit. Once upon a time a painter could get away with simply being a master of his craft. Michelangelo and Rembrandt didn't have to look far for their subjects. Though we like to think we have raised art as a profession above base comercialism (hahahahahahahahah!), from the Renaissance onwards, painting only made sense if there was someone to purchase the painting. So work did not tend to be created and then sold, for this was an inefficient waste of time, but rather only painted if there was a guaranteed buyer - hence commissions. Family or individual portraits, paid for by the sitter; or religious iconography, paid for by the church. So when we look at an old master painting, say Vermeer's Girl With a Pearl Earning, we tend to focus on the artist's wonderful technique, his use of tone, lighting, and brush strokes, and ignore his clever social commentary - if only because there isn't one. No matter. This isn't what portrait painting is about in the Renaissance.

Modern artists have a harder time of it in some ways, then, because they are expected to not only be excellent technicians, but also to be incredibly witty. Taken to the extreme with something like Duchamp's urinal, we have only the idea and no art. I think this is why you so regularly hear comments such as, 'my kid could have made that' or 'yes, but is it art?' And while we'll all draw our own lines as to what does or does not constitute 'art', these two painters, Keith Coventry and Adrian Ghenie, represent all the best possibilities of modern art: bringing together technique and wit in compelling and unique ways, creating beautiful works of art that restore ones faith in modern art.

Coventry typically works in series which is a lovely thing for an observer. It provides a sense of harmony and visual cohesion. Walking into the first room, a gorgeous sequence of paintings following the ROYGBV spectrum catches the eye. It's not until you walk up close that the thick, impasto strokes morph into the face of Jesus. In fact lots of faces of Jesus, as all the paintings in the spectrum of colours are of Jesus - paintings from a recent (2009) series called 'Repressionism'.

The other series I loved was 'Echoes of Albany', painted between 2004-2008. This series of more than 40 paintings is a collective interpretation of the infamous bachelor apartments, Albany, just next to Burlington Gardens. These little snippets of life at Albnany feel like clues to the mysteries surrounding the famous inhabitants of Albany and their equally salubrious lifestyles: paintings of Byron and Gladstone are interspersed with contemporary scenes of prostitution and drug-taking, all in Laura Ashley tones of pink and mauve.

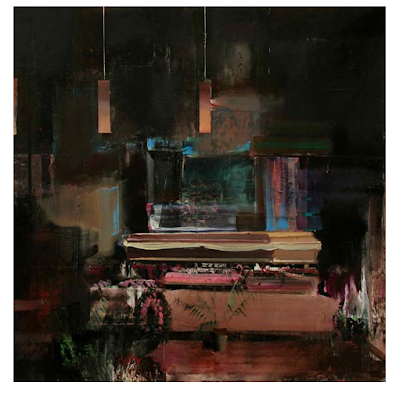

While it was good to see the Coventry, Adrian Ghenie was a revelation. While the exhibition blurb talked about Ghenie's 'enduring fascination with European history, addressed through ideas relating to memory, trauma, and extremism', this almost seems to undermine the exquisite painterly quality and fantastical nature of the subject matter of the paintings.

While it was good to see the Coventry, Adrian Ghenie was a revelation. While the exhibition blurb talked about Ghenie's 'enduring fascination with European history, addressed through ideas relating to memory, trauma, and extremism', this almost seems to undermine the exquisite painterly quality and fantastical nature of the subject matter of the paintings.  Ghenie loves paint, that much is clear. Photographs simply do not do justice to Ghenie's skill as a painter, his exploration of technique and his perfection of a form that works perfectly with his incredibly visual and surrealist form of narrative painting. He drips and pours paint, then scrapes and removes the paint from the surface, building up layers in some areas, eroding in others. Again, the guide talks about Dadaism and Duchamp as being the primary inspirations for the work, but what is so wonderful about the paintings is that they are in no way prescriptive, but rather open to any number of interpretations. A spectacular painting entitled 'Duchamp's Funeral' looked to me like something out of Bram Stoker's Dracula. This fluidity in technique and subject is surprising, beautiful, and inspiring - this is work which must be experienced, not seen - reproductions simply do not do credit to Ghenie's work. Go and see it for yourself.

Ghenie loves paint, that much is clear. Photographs simply do not do justice to Ghenie's skill as a painter, his exploration of technique and his perfection of a form that works perfectly with his incredibly visual and surrealist form of narrative painting. He drips and pours paint, then scrapes and removes the paint from the surface, building up layers in some areas, eroding in others. Again, the guide talks about Dadaism and Duchamp as being the primary inspirations for the work, but what is so wonderful about the paintings is that they are in no way prescriptive, but rather open to any number of interpretations. A spectacular painting entitled 'Duchamp's Funeral' looked to me like something out of Bram Stoker's Dracula. This fluidity in technique and subject is surprising, beautiful, and inspiring - this is work which must be experienced, not seen - reproductions simply do not do credit to Ghenie's work. Go and see it for yourself.

1 comment:

We need more Coventry and less Emin

Post a Comment