Sometimes literary theory just really pisses me off. I love pure philosophy and cultural theory is often intriguing, but the thought of applying Marxism or feminism or some other "ism" to historical events or literary texts (as so often the fashion in academic circles these days) makes me want to slit my wrists. Sure, I can see why it might be interesting to look at the Oedipus myth in conjunction with Freud's oeuvre, but a Freudian reading of Aeschylus (to take but one example) completely baffles.

I've been trying to read Derrida's Limited Inc, but it's slow going. Partly because I feel I need a few uninterrupted hours to blitz through the essays in one go, but also because I feel my brain boiling over with, not quite rage, but certainly annoyance. Admittedly, it's not entirely Jacky D's fault for I find Speech Act Theory on the whole completely ludicrous. How much more ridiculous, then, am I bound to find a deconstructive (destructive?) reaction to an underwhelming theory. Having said that, I feel I ought to finish reading the thing and do quite a lot of thinking before I go mad-dog rabid. After these messages...

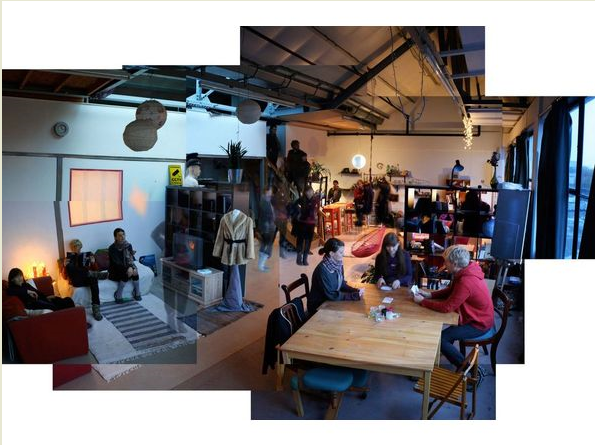

A far more instructive and stimulating experience was to be found at last night's Rip it Up lecture, part of a series at London Met organised by my old boss and now Evening Standard architecture critic, Kieran Long. Paul Domela, the programme director of the Liverpool Biennial, gave the lecture, which focused on the role of public art in urban regeneration and community development in Liverpool and beyond. I've never actually been to Liverpool so I found the talk interesting, not only for what Paul had to say about public art, but also for what he had to say about the nature and history of the city itself.

It's difficult to get a good grasp of the situation simply from one brief lecture but I was completely taken aback by photographs of residential streets with every single house boarded up, and big department stores in the city centre left empty and abandoned. Paul talked us through a variety of projects - from the Carins Street market started by local residents to Ron Haselden's wonderful work creating neon lights out of local schoolchildren's drawings - all of which are grounded in ideas of community engagement and the beautification of depressed and dilapidated areas.

As an artist, a curator, and a critic, I find these projects inspiring and exciting but in the Q and A, Professor Robert Mull, head of the faculty of Architecture at London Met, asked a provocative question that really got me thinking. His question to Paul was that, given the history of civil disturbance in the city (particularly the Toxteth riots), wasn't it possible to offer a reading of these pleasant, feel-good community arts projects as a kind of social and cultural lobotomy: art in place of political action. I don't entirely agree with his assessment, given that the nature, even definition, of community is so ephemeral and changeable. I'm also rather committed to the idea of art as a force for good, for positive social change. But I'd never really thought about art as a substitute for active political action, as if projects that bettered urban areas were a kind of passive non-interaction when contrasted with more direct and active participation of strikes, riots, or protests. Typically, when I'm inclined to make such juxtapositions it's in a Chomsky-esque fashion: sport or television as a substitute for direct political engagement. But I suppose that's what makes a great talk so important - it forces you to check your prejudices and assumptions, to reassess previously held beliefs.

If you have any interest in architecture or urbanism or just in thinking a little bit differently about the cities we live in, do make an effort to attend. Next week's lecture is about Belfast and promises to be just as engrossing, engaging, and essential.

The series continues until 13 January, every Thursday at 6.30pm.

London Metropolitan University School of Architecture and Spatial Design

Spring House

40-44 Holloway Road

London N7 8JL