This piece first appeared in The Architectural Review.

Having grown up in a sprawling American metropolis, for me the best feature of many European cities is their easy navigability. Paris is a particularly wonderful city in which to stroll and for one evening every year, during the Nuit Blanche festival, this quality is exploited and the city gets a dressing up with installations and events, glittering jewels on the wrists of a beautiful woman. Nuit Blanche is one night when the city is entirely given over to the pleasures of wandering and of discovering.

Nuit Blanche is an idiomatic French phrase that literally means ‘white night’. It’s often used to express the passing of a sleepless night, whether because of an uncomfortable mattress or one too many turns on the dance floor. In the case of the first Saturday evening in October, Nuit Blanche refers to the all-night arts festival established by the forward-thinking Mayor of Paris, Bertrand Delanoë, in 2002. Delanoë has done much to bolster Paris’ cultural life: he is also responsible for the annual Paris Plage and the Vélib cycle hire scheme, both much loved by Parisians.

As for Nuit Blanche itself, every year this 12-hour festival – from 7pm to 7am – takes on a different theme. This year saw less a theme, more a concentration around certain geographical hubs – Centre, West, East – to allow visitors more opportunities for ambling.

For its ninth year, Nuit Blanche was curated Martin Bethenod, director of Venice’s Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana. The backbone of the programme consisted of 40 invited artists, but like any good arts festival, a fringe programme has also sprung up and many artists and galleries use the exposure to organise their own installations throughout the city.

Given that the festival takes place during the hours of darkness, it is hardly surprising that so many of the installations experiment with light. Of these, the most effective was Thierry Dreyfus' deceptively simple light installation inside the Notre-Dame de Paris. Dreyfus’ piece, Offrez Moi Votre Silence, was remarkable for its ability to force a new reading of a familiar building. Switching off all city lights around the church’s exterior, Dreyfus installed a series of internal floodlights which dimmed and brightened in a gentle rhythm, like a lung breathing inside the Notre-Dame. When viewed from outside, the church was dark save for the glowing stained glass windows.

Perhaps Paris’ most famous lighting designer, Drefus made an eloquent comment in a 2005 New York Times interview which coincided with the reopening of the Grand Palais: ‘What is the sense of lighting buildings at night to show what you see during the day? You have to bring another dream.’ The installation is testament to the strength of Dreyfus’ vision. On this evening the Notre-Dame feels different: less like a space for sacred worship, more a place to appreciate the power of secular creation. Dreyfus’ breathing light lungs have transformed the overwhelming grandeur of the church into a space that feels far more unified, serene, and familiar. Shock and awe has been replaced by feelings of profound calm and composure: it’s a remarkable transformation.

Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, of recent birds-in-the-Barbican fame, exhibited an older project, Harmonichaos from 2000. One of the perks of Nuit Blanche is that you get to snoop around buildings not regularly open to the public. Boursier-Mougenot’s comically-sinister, harmonica-playing hoovers are installed in a salon in the beautiful Hôtel de Lauzun, on the banks of the Seine. A private townhouse, the Hôtel was constructed during the reign of Louis XIV and its ornate and rich interiors have seen hardly a change in the following centuries. The sumptuous room where Boursier-Mougenot's hoovers are displayed serves as a delicious foil to the late-80s aesthetic of the old hoovers, and the weezing whine of the harmonicas creates an atonal, modernist kind of symphony.

Respite from the demands of this sleepless night were provided by Louidgi Beltrame’s enlightening film about Gunkanjima, screened in the École Nationale Supérieure D'Architecture in Belleville, an area increasingly known for its community of up-and-coming artists in eastern Paris. At 5am, Beltrame’s hypnotic film of Gunkanjima’s ruined buildings was most welcome. In all honesty, it’s difficult to judge the accuracy of my response to the film given the circumstances, but it was exactly what was needed at the time: slow-moving images of a dystopian-Disney fantasy, a coal-mining island long since abandoned. Off the coast of Nagasaki, the island was populated by workers from 1887 to 1974 and then left to crumble thereafter. Beltrame’s camera makes no ideological or moral statement; it only shows what’s left of this bizarre island, which resembles the ghostly remains of a depressing work camp. The pull of the place is undeniable and Beltrame has done a great service simply in bringing it to light.

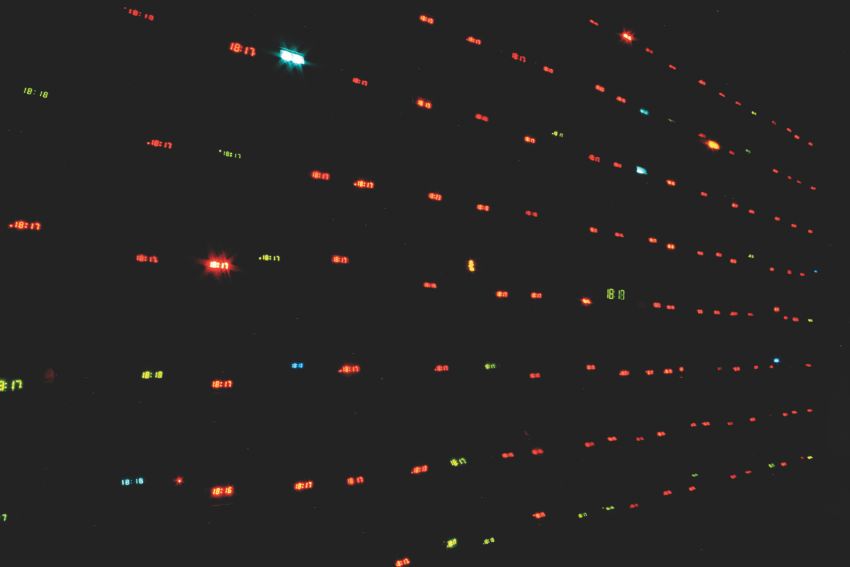

Though not as successful as it might have been given that the space was too small and that a gaggle of teenagers seemed to have used it as a bed for the night, Fayçal Baghriche's piece, Snooze, brought Nuit Blanche to its end. A pitch-black room in the Hôtel d’Albret was filled with 300 alarm clocks resting on shelves lining one wall. The clocks ticked away all throughout the evening, until at precisely 7am, the alarms all went off in (near) unison. While the noise of the clocks wasn’t quite as deafening as I expected, the idea of trying to arrive on time for an alarm clock to go off is playful and amusing. As is the notion of the alarm clock as an Alice-in-Wonderland-type symbol: 300 alarms go off and one turns from night-time dreamer back into day-time doer.

No comments:

Post a Comment