This piece first appeared in the Architectural Review

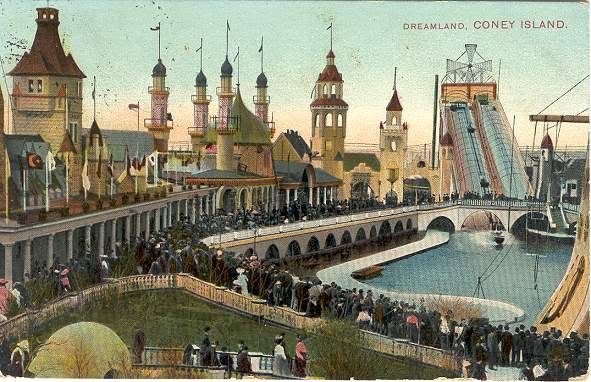

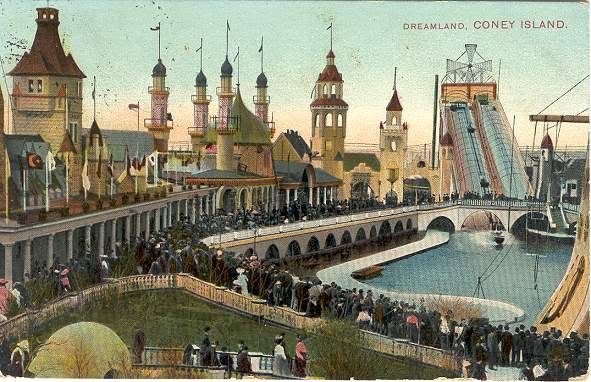

The eponymous Dreamland of the Pompidou’s recent exhibition refers to the Coney Island theme park, forerunner to the Venetian canals and Egyptian pyramids in modern-day Las Vegas, built in 1904, burnt down in 1911 and never rebuilt. This is a thoughtful exhibition on the nature of architectural dreamscapes within societies with ever-increasing amounts of leisure time. It covers a considerable sweep of history, from the turn of the twentieth century in New York to modern-day Dubai, and many well-known names appear: Archigram on the instant city, Scott Brown and Venturi on Las Vegas, Koolhas on New York.

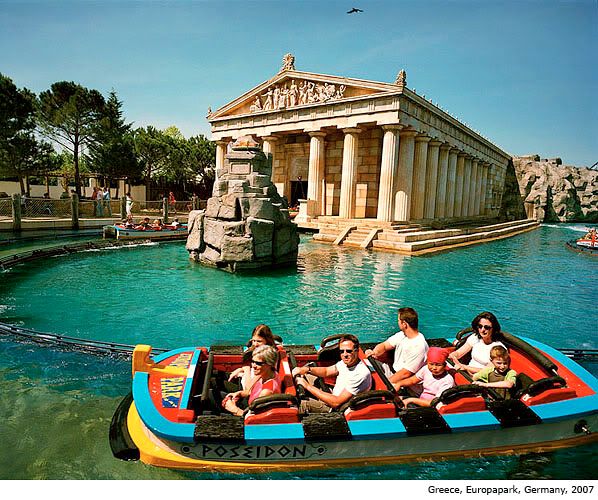

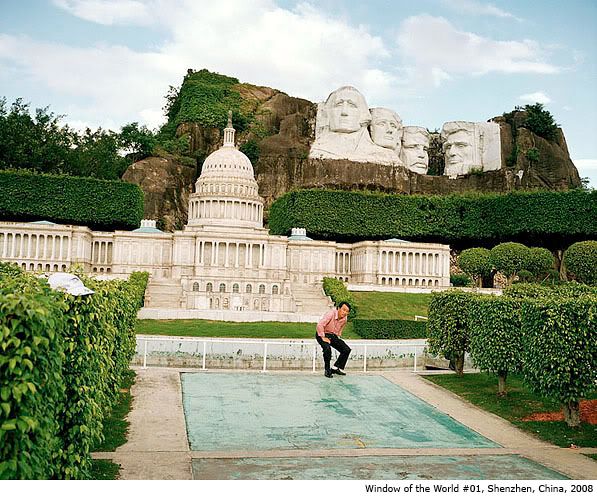

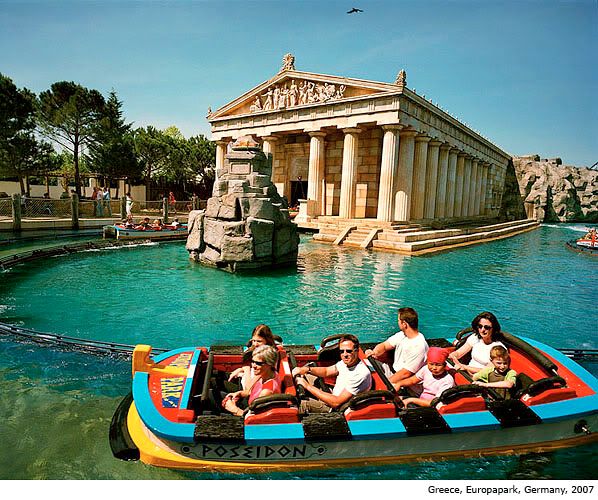

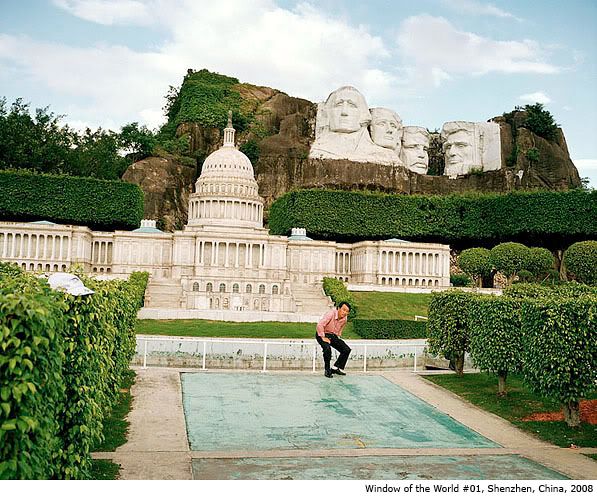

But the exhibition turns truly provocative when lesser-known names materialise, particularly in the section themed around the concept of copy and paste. It’s nice to see a new generation of artists playing with Susan Sontag’s observation that tourists photograph unfamiliar places as a kind of unthinking defence mechanism, to cope with the unfamiliarity of being in a new place. Seung Woo Back’s photographs of familiar monuments transported to unfamiliar locations raise the important question of whether context matters, despite the fact that the images are not staged but taken at Aiins World theme park in South Korea. Is the Eiffel Tower still the Eiffel Tower if it isn’t in Paris? The answer seems obvious, but take perhaps a more culturally loaded monument, say, the Elgin Marbles, and the question becomes more difficult to answer. Woo Back, along with the vivid, staged images of Riedler Reiner, exploits the illusory nature of theme parks for maximum visual impact. Their images directly confront the idea of the theme park as a self-contained, miniature version of the entire world and make one uncomfortable with the premise of theme parks as a replacement for genuine architectural exploration.

|

| Seung Woo Back, Real world I no.01 |

|

Seung Woo Back, from the Real World series

|

|

| Riedler Reiner |

|

| Riedler Reiner |

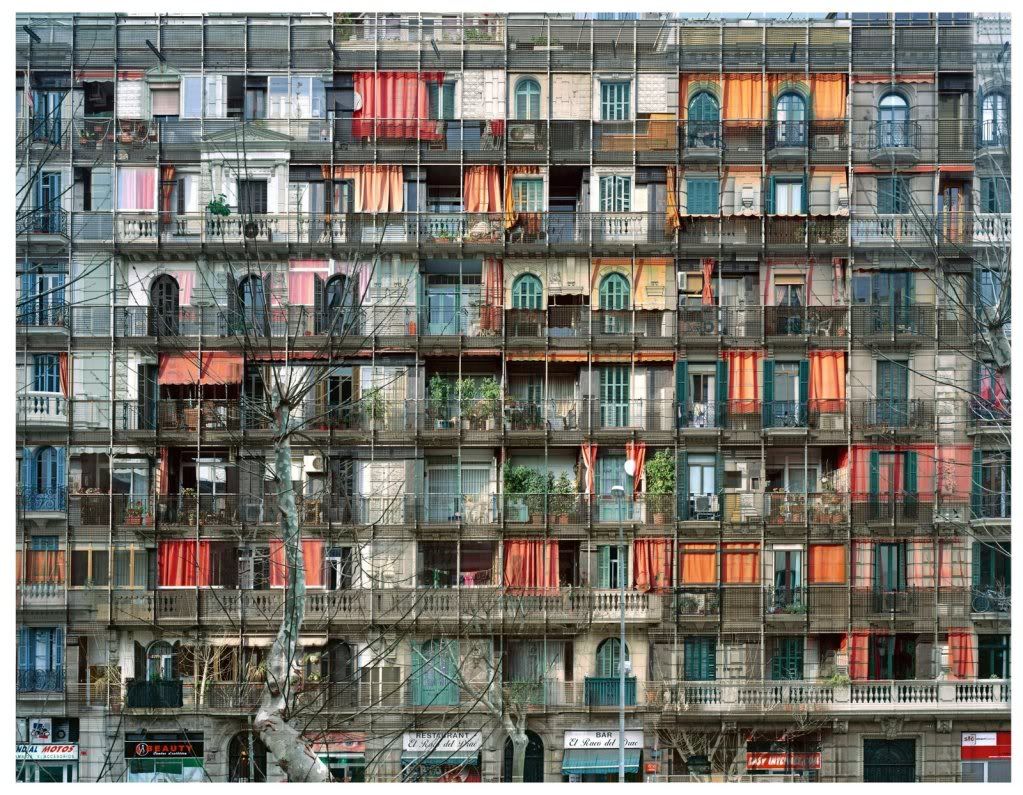

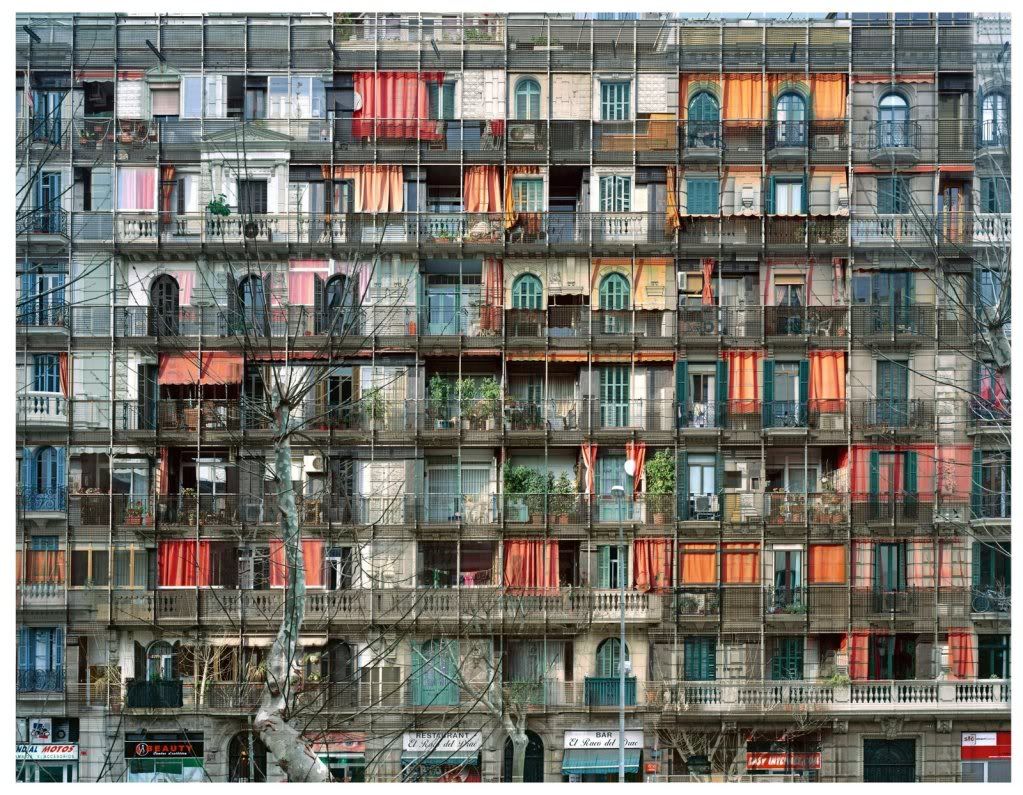

Most of the work in Dreamlands poses a direct challenge to the idea that architecture is a lasting achievement. Not that this is in any way belittling to its subject, for the exhibition celebrates the temporal and the transient in both man and his environment. For what is man if not temporal, unstable, changeable? Certainly, we respond to the monolithic and the conspicuously permanent in buildings – the art in the exhibition demonstrates that as well – but we must also be aware of this most human need for adaptation and change. This is taken to its most eloquent and literal conclusion within Yin Xiuzhen’s clever series of portable cities: a miniature, physical, plush toy representation of an entire city, in this case New York, stitched into a suitcase. Stéphane Couturier’s beautiful photographs of façades also consider the temporal nature of urban environments: how we simultaneously construct and destroy within the urban environment. Scaffolding is just scaffolding, but in this context it represents its own kind of dreamscape as a promise of the future.

|

| Yin Xiuzhen, Portable Cities, New York |

|

| Stéphane Couturier, Barcelona, Avenidad Parallel #2 |

|

| Stéphane Couturier, from the Melting Point series |

Dreamlands responds to JG Ballard’s challenge of the endless leisure and frantic consumerism of western spaces and mirrors the central theme of Jem Cohen’s excellent 2004 film on shopping centres, Chain: no matter where you are in the world, the typology of these spaces adheres to the same function and the same aesthetic. These visions of falsified utopias, while depressing in their original purpose, make for fascinating viewing within the context of a museum space, itself a kind of ‘dreamland’. Shopping malls and theme parks both represent a loss of traditional spatial and geographical reference points: here we have the crux of globalisation.

While the instinctive reaction to all this is to suggest that architecture has some catching up to do, how does one create a localised utopia? Utopias and dreamlands by their very nature are generalised, universal ideals. Throughout this exhibition the imaginative responses, demonstrated by artists and architects alike, to these faceless, falsified utopias suggests that it isn’t so much the representation of the dreamland that needs re-evaluating as it is the very ideals of Western society.

1 comment:

Amazing pictures. Sorry about your cat.

Post a Comment